I am sitting in a colorful little cafe in Bogotá’s trendy Zona G. Outside a steady rain is falling. Bogotá is a mountainous city with chilly air and frequent showers. Much like in Britain, it’s wise to always have an umbrella in hand (or purse). Today, fittingly, the weather is perfect to indulge in an afternoon coffee crawl.

I am ready to get caffeinated.

I meet with Karen Attman, an American expat-cum-Colombia coffee expert who arrived in Bogotá years ago and now educates on all things Colombian coffee. She’s going to introduce me to a variety of styles and roasters to take the pulse of the specialty coffee scene, which is growing exponentially in Bogotá and countrywide.

We start at Colo, which ended up being one of my favorite roasters in Colombia. We sit at the counter with the barista, David. Karen starts by saying, with a slight laugh, “You are going to hear this phrase over and over again. Colombian coffee is the best. Of course, Colombians are the ones saying that, but it is true.”

She expands, “It all starts with the species used, Arabica beans, that generally produce better flavors and more complexity than the commercial Robusta. In fact, only Arabica can be exported from Colombia to protect the reputation (and prices) of Colombian coffee. Colombians recognized the value of quality coffee right from the beginning. While other countries (Brazil and Vietnam, to name just two) have focused on quantity for at least part of their production, and used the lower quality Robusta beans.”

Karen pulls out a flavor wheel, similar to those used for wine and chocolate, two of my other favorite things in life. I immediately know that this is going to get deep rather quickly.

“Like wine, there are aromas, structure, acidity to consider. It depends how you roast the beans, grind them, the brewing method and extraction.”

Oh yes, I feel my inner coffee geek emerging. This is all so interesting, fun, flavorful.

To get the tasting started, at my request, I want to try the geisha coffee, a bit of a legend in the coffee world. The Geisha variety rose to fame when Hacienda La Esmeralda entered it into the Best of Panama competition in 2004–and won. Then they won again for a further five consecutive years. Everyone was completely floored by the Geisha’s fragrant notes and citrusy floral sweetness. However, Geisha isn’t exclusive to Panama – it’s also grown in Ethiopia, Tanzania, Malawi, Costa Rica, Peru, and Colombia.

When I mentioned I was headed to Colombia to taste coffee, my serious coffee aficionado friends wrote:

“Liz!!!! Must. Try. The. Geisha.”

and

“Girl, it’s God in a cup.”

Well, then it must be good. Noted.

Geisha is best brewed as a filter, as its subtlety is less suited to the harsh pressure of an espresso machine (although full disclosure, I also tried it as an espresso and it was delish). Geisha most definitely does not shine with a blanket of steamed milk poured over it. That is total sacrilege. And to add my two cents on this matter, I personally feel that putting any milk or sugar in a specialty coffee is total sacrilege. There…I’VE FINALLY SAID IT!

In Geisha coffee’s case, let’s see, this would be akin to putting some ice cubes and strawberries in your Grand Cru White Burgundy. Ummm…NO. Please don’t do that.

David prepared the Geisha in a V60 (pour-over). He worked in silence with the precision of a scientist conducting an experiment from weighing the beans to grinding them, taking the water temperature, and then expertly wetting the grinds. Once poured, the coffee looked almost tealike. Not at all what I expected.

The signature of a good Geisha is the floral aroma. I was totally blown away by its perfume-like quality. It smoothly transitioned in the mouth into this sweetness, almost honey-like, with a delicate acidity that kept it feeling “alive”. It lingered, like a fine wine, just the right amount of time. It was so flavorful and light, unlike any coffee I had ever tried before. It somehow reminded me of the “Pinot Noir” of the coffee world.

Finally, I had finally lost my Geisha coffee virginity.

Karen orders another round, different bean and different preparation (Aeropress). I need more clarity as to the “specs” of a perfect cup of coffee and how I should be making it at home.

Me: Confession time. I think I am scalding my coffee in the French Press with water that’s too hot and pouring too fast. How should a perfect cup smell, taste, feel?

Her: That is a really open question about “perfection”, given the huge variations in fragrance, aroma, body, and flavors in the world of specialty coffee.

Me: Enlighten me with some general parameters, please.

Her: There is no one perfect type of coffee. (Amen). There are lots to choose from. That means you can choose a coffee with a light body, complex yet subtle flavors, and a prolonged finish. Or you can go for a heavy body, profound flavors, and a surprising finish.

Me: (Lighting up) For sure. This is sure sounding a lot like wine (in my head I am screaming…Yes! Wine! Familiar territory!)

Her: It is. It depends on the type of coffee like the species and variety, but also how it was processed, roasted, and brewed.

Me: I just want to have palate-bending coffee every morning now that the bar has been set high with that Geisha. How do I do that?

Her: Learning to brew coffee is an art that takes some time to learn. With practice, a person learns how varieties such as Geisha or Bourbon affect the results in the cup. They know what to expect from a natural processed coffee as opposed to a washed coffee, and they understand what a light roast will do to the coffee. And of course, how to prepare all of this at home.

Me: Right, right…of course!

I try to act like I just followed everything she just said, but in actuality, I desperately need a glossary and now, I damn well know I have been scorching the shit out of my coffee every morning.

We walk in the rain through the pretty residential area near Parque del 93, a stylish area of Bogotá. Our destination is Azahar, one of the specialty coffee pioneers in Colombia that have blazed the trail both in fair trade, roasting style, and it’s cool cafes across town.

With nearly half a dozen beans and styles, we order a Chemex of their “Frutal” blend. I am particularly intrigued by the idea that coffee, like wine and chocolate, comes from a fruit. My theory is that if processed correctly, I should perceive that fruitiness in a cup of coffee.

The cafe is extremely busy and we luckily find a table a bird’s eye view of the tattooed baristas pumping out orders.

As we sip this coffee, deeper in body, aromas, and flavors than the previous ones, it is most definitely “fruity” (think figs, plums, dark fruit). Karen goes deeper into why Colombian coffee is so good, but in a word, it’s the terroir.

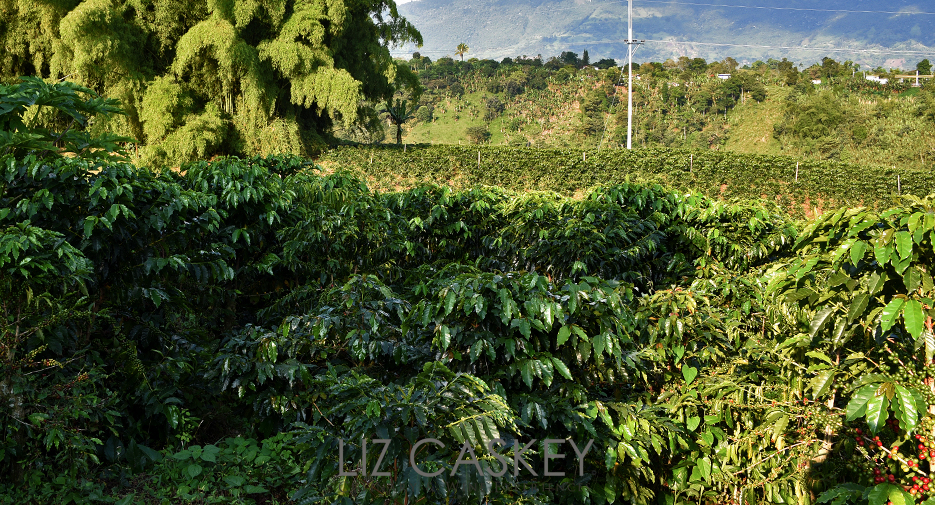

All of Colombia is within what is called the Coffee Belt, that region of the globe where coffee can be grown. Colombia also has plenty of mountains which is essential for growing Arabica coffee. Thus, Colombia can produce coffee from north to south, and pretty much from east to west. Add to this climatic Eden an abundance of rich volcanic soil and that most of the coffee is shade-grown, handpicked, and processed with care, you can see why it’s just so good.

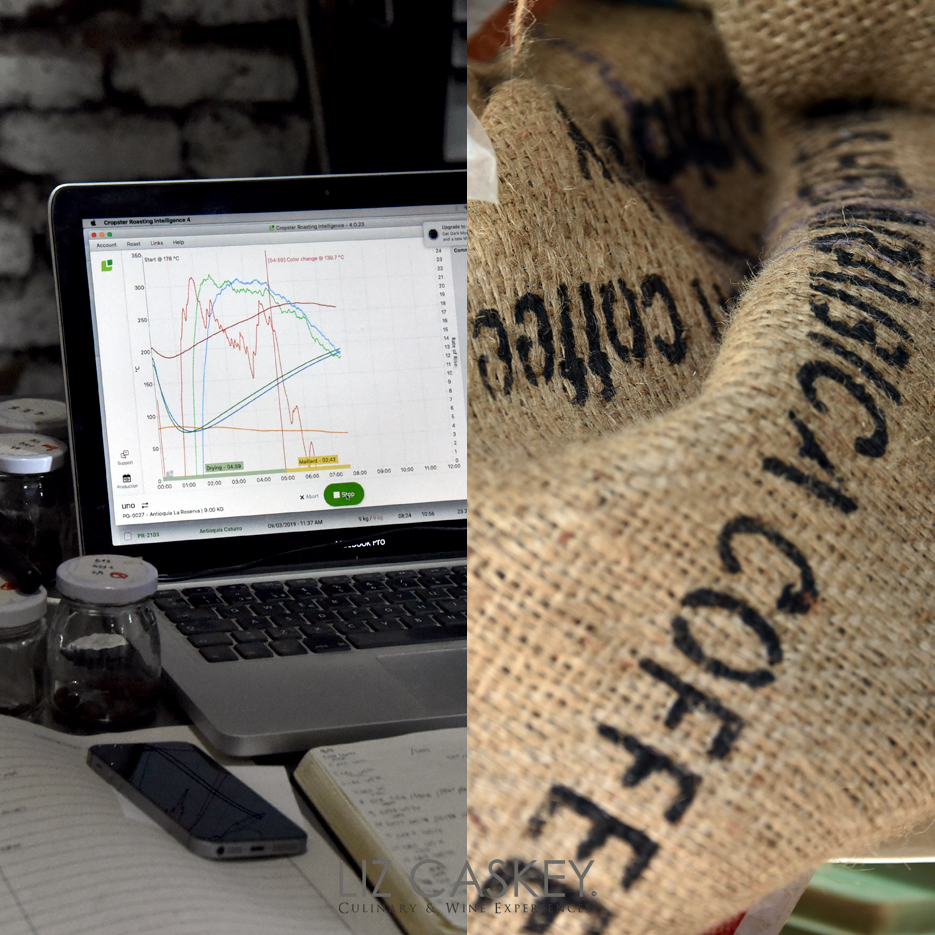

“But that is only the beginning,” she continues, “Then comes the roasting, much like the winemaker and wine. Roasting is an art. And frankly, not everyone gets that art right. However, when taking into account only good quality coffee and roasters, there are still a thousand differences between one company and another.”

She launches off some questions to consider like: Where is the company sourcing the coffee from? What types of processes does the farmer use? What does the company expect from a coffee? Those are all determining factors. However, in the end, the greatest factor is the roaster. A skilled roaster is key.

We discuss why finding a company/roaster that you love is vital for coffee pleasure and alignment. She really makes me think about what style I like, what draws me in flavor-wise. Hmmm. Am I looking for lighter flavors and a more subtle experience? Or for fruity, high acidity coffees? Do I look for intense flavors? There are no set answers (like in everything in life) and she encourages me to taste as much as possible.

And I did just that.

I hit numerous specialty coffee spots in Bogotá. After, we traveled to the coffee mountains of the Quindio region. We tasted in Medellin in the region of Antioquia. No two coffees were alike. Some were sweet. Others were floral. Some were tea-like (those geishas and bourbons). Some tasted like lemongrass. Others were Mocha-kissed and caramel-laden.

After a few weeks in Colombia, I really had become a real coffee aficionado–and a caffeine addict. But I had also achieved honing my taste preferences. Pretty much, they are the same as in wine, chocolate, and food. I like aromatic and light (citrusy or floral), medium body with presence but not too overbearing. Great acidity with maybe a touch of sweetness (sometimes, not always). And the major dealbreaker, NO BITTERNESS. EVER. The bitterness is actually a defect, as many roasters explained, and hallmark of a “burnt” coffee.

This topic of “dark roast” coffee, which I will tackle in a future post, is so typical of Starbucks and much of what of Europe is drinking as “good coffee” (looking at you, Italy). The coffee is actually over-roasted, and even burnt, in many cases. Of course, with the inherent bitterness from over-roasting, clearly many people will want to balance (or cover) that with sugar and milk. I no longer accept the general perception that coffee has a natural, slightly bitter aftertaste after my Colombia coffee education. People, it is not the case. It’s 100% a roasting issue.

I arrived home in Chile, quite literally, with a whole suitcase of coffee. We’ve been drinking it for the past few months across regions, beans, producers, and roasters. We are constantly amazed by how different each coffee is.

And for those wondering, I finally did up my brewing game. I got a nifty Hario V60 glass pour-over (a favorite of many baristas) that yields a coffee that is so much more flavorful. Truthfully, I have nearly abandoned the French Press (my husband still uses it, he likes a more robust morning coffee). I relish the whole ceremony of grinding, weighing, preparing my coffee slowly, and savoring the aromas as it’s coming to life.

I also love knowing the origin of my coffee. There’s so much more meaning when you know the place where it’s grown, the people behind it, and its journey from bean-to-cup.

Most definitely, this is the beginning of a beautiful love affair with Colombia and its specialty coffees.