I am sitting on a very cush couch sipping a velvety Malbec, noshing on some cheese, and talking to Walter Bressia. Walter is the owner, founder, and winemaker of Bressia, a boutique winery in Mendoza. The topic of discussion? Mature wines—and why these are increasingly rare bichos in the marketplace.

Before I let you guys eavesdrop on part of this conversation, first some background on Walter to understand his perspective on this topic. When I first met Walter almost three years ago, the current winery was a little cement block on a shady dirt road off Route 7, the International highway that crosses the Andes into Chile. It was as garage a concept as they come. All the tanks were huddled in the middle of the room with the barrels against one wall. Bottling and labeling were stacked on a work bench against the other wall. It was tiny but efficient. Outside, there was a hole in the ground for the future wine cellar.

Fast forward now to a petit yet high tech, modern bodega with an underground barrel cellar, beautiful natural light offices, and a cozy reception area to receive guests like myself and my husband. Today, Walter’s family is fully involved in the distinct roles of running the winery business from winemaking to tourism and exporting.

Bodega Bressia is located on a 49-acre estate in the area known as Agrelo of Mendoza, about 30 minutes south of Mendoza city and relatively close to the Andes. Walter is a veteran in the wine business having worked with some of Argentina’s big boys before realizing his lifetime dream of creating his very own boutique winery.

The production here is small. Try a little over 2,000 cases. Bressia painstakingly oversees the details of all the parcels that are farmed, both on their estate and high quality produces sourcing additional grapes used at harvest. Everything, and I mean everything, in this winery is handcrafted. Although they have more space now, this is a family run, boutique operation. The winemaking philosophy here is non-interventionist and stylistically speaking, I would really characterize this wines as smooth, slightly sweet, and just delightful. If you believe the old addage (and I do), that wines are a reflection of the winemaker’s personality, then this would be completely accurate of Walter and his humble, sweet, delightful nature.

This brings me back to our conversation on mature wines. Bressia makes mature wines. So what does that mean in today’s every changing wine market place? Basically, releasing a new wine into the market when it is mature enough to be enjoyed properly with no aging required, only optional. Wine is of course made from mature grapes, but in the process of turning it into wine and the “final product”, wine also reaches a point of maturity from where it can be drunk. Imagine this like buying tomatoes: pale red and tasteless or red, juicy gems. I also do not want this concept confused with aging wines. That is totally different. With aging the objective is to see how a wine evolves over a period over time. Once again, maturity of wines simply is looking at their “ripeness” when they are released into the market for consumers.

Walter and I reflect on how many wonderful boutique projects and wineries that suddenly get high scores from Spectator or Parker, catapulted to cult status, start experiencing some big issues around this. All of a sudden, there is a huge demand for their wines and they only make, say, 3,000 cases. Should we hold the wine that extra year to get it to maturity or should we release it sooner? Well, that seems easier and more immediate than increasing production. It is a risky decision because essentially, market demand is overriding a stylistic, and in my opinion, potentially a quality decision.

To highlight this, what happens if you buy a great wine like say Achaval Ferrer Quimeira 2007, but really that is a wine whose maturity would dictate it be released in another year. Now, maybe as a wine geek, you buy it knowing this and are willing to sit on the wine until then. However, what if you are just an average wine loving dude who wants to drink a bottle to remember a trip to Argentina and has no clue about this? I’ll tell you what happens. They open it. They don’t decant it. The wine tastes, um, different. Muted, less expressive, very tannic and acidic-punchy. It is certainly not bad but not as spectacular as they remember it at the winery. Or maybe they have never tried it; and it does not live up to all the hype, price tag, and expectations those two things generate.

This is something that is not just happening with fine wines, it is happening with simpler wines and even the cheap-and-cheerful varieties, although here the par is lower since you have a different price consideration and consumer. To date, I have not yet seen a wine bottle with a disclaimer tag on it saying, “ripen for 6 months for ideal drinking”. Once again, this is not aging, this is maturity of the wines. Why would I want to buy a hard-as-a-rock avocado for a recipe for guacamole I want to make tomorrow? Why would I buy green plums and have to wait for them to ripen to make a cake or, not knowing they are green until I bite into one? It just doesn’t make sense. But nobody seems to be talking about this topic in these terms.

Well thankfully, Bressia is conscious of this and makes wines that are released that are fully mature. This may not be the best economic decision for them as a winery, but they are more concerned about delivering a stellar product. To give you an idea of their wines, in a broadstroke sense, they are like biting into a juicy, sweet black plum with juice that dribbles down your chin. It is like sipping a bowl of ripe summer berries, perhaps with some dark chocolate grated on top, or a shot of cassis liquor drizzled over them. They feel like velvet in your mouth. The oak is present so the wines tend to need a little air to let them stretch their legs and meld together. They are soft, mellow, elegant.

As I converse with Walter, we are drinking Monteagrelo, one of my favorite Malbecs from Mendoza. It is full-bodied, juicy, and a blend from three vineyards in Agrelo and Lujan de Cuyo (closer to the city). This is a concentrated wine with an inky purplish color. It has a very sensual nose full of mocha and vanilla scents and black plums. In the mouth, it has presence, this is not a wimpy wine, definitely tannins happening here. But it is smooth, elegant. An image of a powerful, beautiful woman dressed in a flowing gala dress appears to me, which I think embodies its personality of strength, charisma, and finesse. I am all over the cassis flavors in this wine too. After having drunk a couple bottles of this on different occasions, it is one of those wines that the decanter is empty and you think, “how’d that happen so Fast?” And this wine is a steal at about US$27.

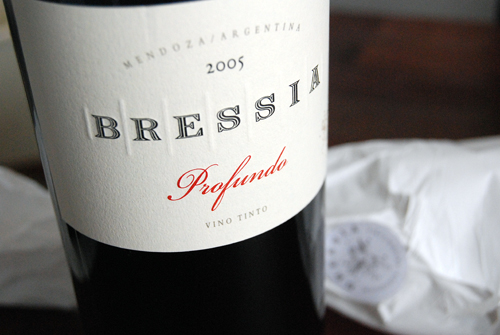

The next level up at Bressia, at US$40, is Profundo, meaning profound in English. This wine is all about complexity. The concentration and nose of this wine is just awesome. Made from 50% Malbec, 30% Cabernet Sauvignon, 10% Merlot, and the spicy addition of 10% Syrah, the nose of this wine is seductive and rich. Lush, perhaps is the best description. It reminds me of a blackberry patch with something slightly herbaceous and an earthy sweet note like vanilla bean. In the mouth, it is a chewy wine but that finesse (Walter’s mano, style) is ever present. The wine undresses itself as it breathes. I think it is best to open it, try it, decant it. Drink it slowly, preferably with somebody whose company you love and will appreciate it. Very memorable–and only a few hundred cases made. Worth seeking out (we have one left in our cellar, yeah!).

In the United States, you can get many of Bressia’s deliciously ripe wines from an import company called, fittingly, Bottled Poetry, located in Texas. You can also contact Kysela Pere e Fils for distribution in the whole market of their wines. They are really worth the effort to seek out. Or if in Mendoza, take a detour to visit these folks, get to know their family, the wines, and what a mature wine is really all about. In a word, inspiring.